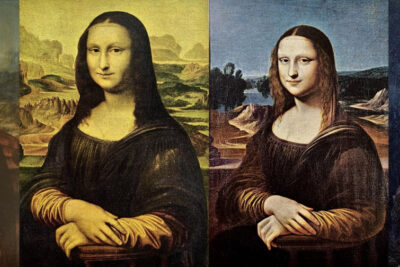

Versions Mona Lisa: Interpretation, Replica, and Reinvention of the Iconic Masterpiece

Art is rarely just about what we see on the surface. Behind colors, shapes, and compositions often lie deeper messages—coded visual languages that connect the viewer to universal ideas. This is the essence of symbolism in art. From ancient cave paintings to contemporary works, artists have embedded layers of meaning into their creations, inviting interpretation and reflection.

The Symbolism in Art category explores how symbols shape visual culture, examining their historical origins, cultural variations, and modern relevance. By learning to recognize symbols, viewers can enrich their appreciation of art and connect more deeply with its hidden messages.

Symbolism refers to the use of images, objects, or motifs to represent abstract ideas or concepts. A dove may symbolize peace, while a skull might represent mortality. These meanings are not arbitrary—they reflect cultural traditions, religious beliefs, and artistic conventions.

For artists, symbolism serves multiple purposes:

Communicating ideas without words

Conveying spiritual or moral lessons

Encoding political or social commentary

Engaging viewers through interpretation

Symbols were crucial in ancient art, where literacy was limited. Egyptian hieroglyphs, for example, combined text and imagery to tell sacred stories. In medieval Europe, Christian art was filled with iconography: lambs for Christ, lilies for purity, and halos for holiness.

Renaissance painters like Jan van Eyck and Botticelli used objects with double meanings. In The Arnolfini Portrait, a dog represents loyalty, while fruit suggests fertility. Baroque art expanded this tradition with vanitas still lifes, where candles and skulls reminded viewers of life’s transience.

In the 19th century, symbolism became a formal artistic movement. Artists such as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon emphasized dreams, mythology, and the subconscious, using imagery to convey psychological depth.

Surrealists like Salvador Dalí embraced symbolism through dreamlike imagery—melting clocks, burning giraffes, endless deserts. In contemporary art, symbols often take new forms, from digital memes to conceptual installations, reflecting today’s cultural anxieties.

Skull: Mortality, the passage of time (memento mori).

Apple: Knowledge, temptation, or sin (from biblical tradition).

Mirror: Vanity, truth, or self-reflection.

Butterfly: Transformation, resurrection, the soul.

Owl: Wisdom, mystery, or darkness.

Colors:

Red: Passion, power, danger.

Blue: Spirituality, calm, or sadness.

Gold: Divinity, wealth, or immortality.

These meanings can shift across cultures. For instance, while white often symbolizes purity in Western art, it can represent mourning in Eastern traditions.

Studying symbolism is essential for art appreciation:

Deeper Engagement: Unlocking symbols allows viewers to understand artworks beyond aesthetics.

Cultural Insight: Symbols reveal values and beliefs of the societies that produced them.

Continuity Across Time: Many symbols remain consistent across centuries, connecting us to past generations.

Personal Interpretation: Viewers bring their own experiences, making symbolism a dialogue between artist and audience.

Interpreting symbols is not always straightforward. Some symbols are universal, but others are highly contextual. For example, snakes can symbolize evil in Christian art but represent healing in Greco-Roman tradition.

Therefore, art historians often combine visual analysis, historical context, and cultural knowledge to decode meaning.

The Arnolfini Portrait (1434, Jan van Eyck): Filled with symbolic details, from the dog of fidelity to the single candle symbolizing divine presence.

The Persistence of Memory (1931, Salvador Dalí): The melting clocks symbolize the fluidity of time and the instability of reality.

Guernica (1937, Pablo Picasso): Horses, bulls, and broken figures symbolize suffering and chaos during war.

The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1500, Hieronymus Bosch): A masterpiece of enigmatic symbolism, blending moral lessons with surreal fantasy.

Look for recurring objects or motifs.

Consider historical and cultural context—what might the image have meant in that time?

Analyze placement and scale—symbols are often emphasized through composition.

Explore secondary sources—museum labels, art criticism, and scholarly articles can provide clues.

Reflect personally—symbols are powerful because they also invite individual interpretation.

Why did artists use symbols instead of direct messages?

Symbols allow artists to communicate abstract ideas subtly, especially in times when direct expression could be censored.

Are symbols universal across cultures?

Some symbols, like the sun or water, appear globally but often with different meanings. Others are specific to certain traditions.

What is the difference between symbolism and allegory?

Symbolism uses a single image to represent an idea, while allegory involves an entire composition structured around symbolic meaning.

Do contemporary artists still use symbolism?

Yes. From street art to digital media, contemporary artists continue to employ symbols—sometimes drawing on tradition, other times inventing new ones.

Can colors themselves be symbols?

Absolutely. Color symbolism is one of the most powerful and consistent forms of visual language in art.

The Symbolism in Art category is a gateway to understanding the hidden layers of meaning that enrich visual culture. From medieval religious symbols to surrealist dreams and modern conceptual art, symbols challenge us to look beyond appearances and engage with deeper ideas.

Whether you are a student, researcher, or casual museum-goer, exploring symbolism allows you to unlock stories that might otherwise remain invisible. By learning this visual language, you gain a richer appreciation of the complexity and universality of art.

5 articles

Versions Mona Lisa: Interpretation, Replica, and Reinvention of the Iconic Masterpiece

Express Yourself in Art: Creativity, Techniques, and Personal Expression

Color Symbolism in Art: How Colors Convey Emotions and Ideas

7 Hidden Meanings Behind Famous Artworks: A Deep Dive into Symbolism in Art

The Symbolism of the Mona Lisa: What Her Smile Really Means